Information is one of the greatest weapons in the age of modern conflict, where warfare is no longer restrained to physical boundaries but now often plays out on the internet’s “invisible battlefield.”

Manipulating information to subvert one’s enemies is not a new tactic, but it has reached new levels as the internet and social media have granted an almost instantaneous way to disseminate information to audiences around the world. As a result, many governments have seen the advantage of this unregulated information environment to influence the affairs of their adversaries with greater ease.

This has turned cyberspace into a mess of truth, lies, and rumors that are carefully crafted by state actors to manipulate public discourse.

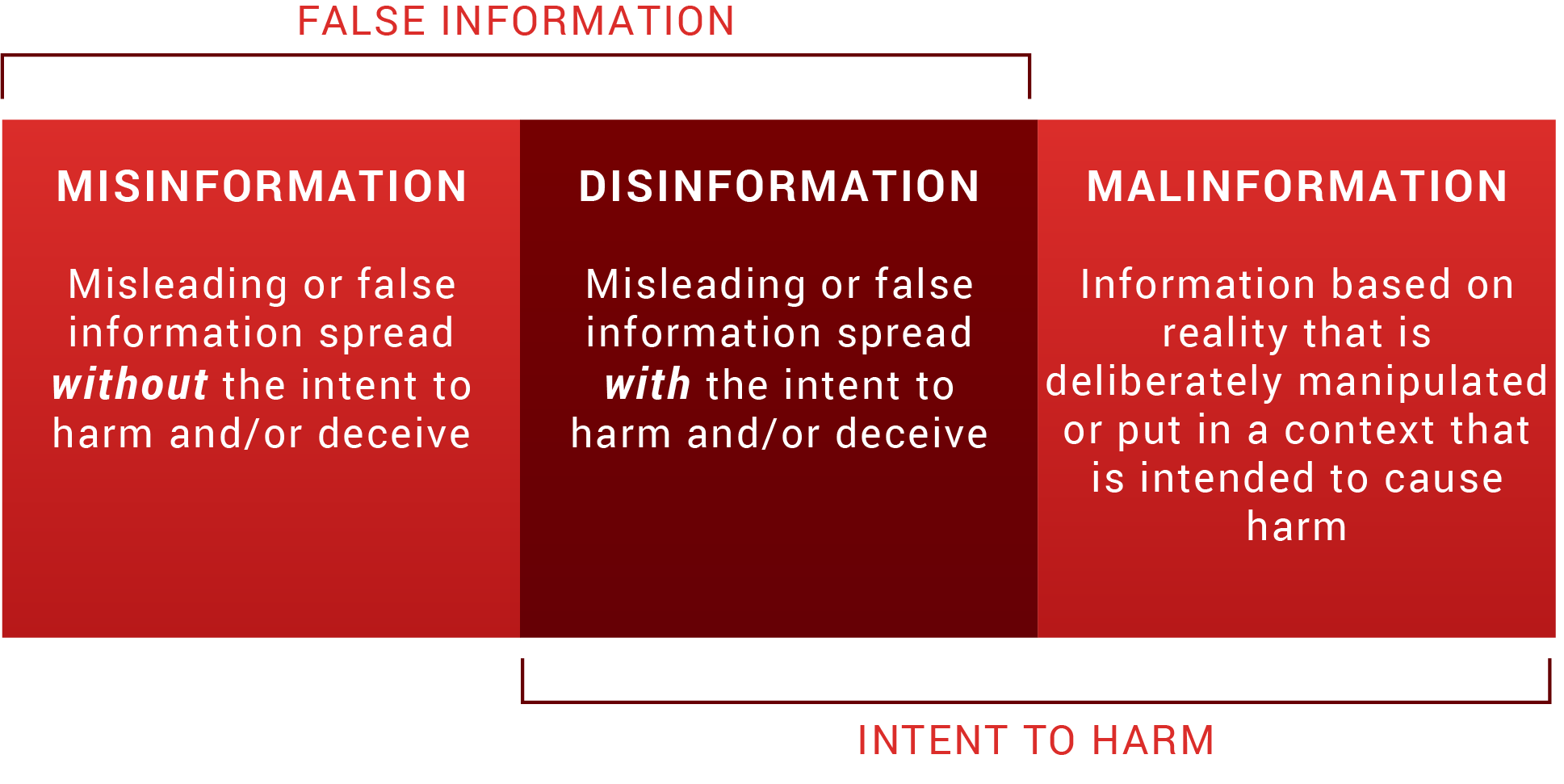

False or misleading information can take a variety of forms, but most commonly falls under one of three categories: misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation.

Misinformation vs. disinformation vs. malinformation

Misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation are often confused with one another, so it’s important to clarify the differences in order to understand the impacts each can have.

Misinformation and disinformation are both false information, but misinformation is spread without the intention to harm and disinformation is spread with the intention to harm. Malinformation, on the other hand, is information that is based on reality but is deliberately manipulated or put in a context meant to inflict harm, like real documents released right before an election to harm a person’s chances of being elected.

As pointed out above, intention is what differentiates misinformation vs. disinformation. While the spreaders of misinformation don’t have any alternative motive behind sharing inaccurate information – or may not even be aware of the inaccuracy of the information at all – those who spread disinformation are deliberately intending to mislead others.

The goal of controlling or spreading disinformation is often to have a specific effect among a target audience and/or manipulate the way people perceive reality. Nation-states continue to weaponize disinformation in order to influence opinions, create confusion, and polarize the population of an adversarial target. This could be through fake news stories spread through state-aligned media outlets, like Russia’s RT and Sputnik. Sputnik; or through social media posts propagated by online bots, like the Twitter bots used to spread propaganda around the 2016 U.S. presidential election; or paid marketing on social media platforms, which is a popular tactic used by Chinese threat actors.

What is disinformation in cyber?

Nowadays, cyberspace is the primary way in which disinformation is generated, disseminated, and consumed. Taking this into consideration, disinformation operations are actually, more often than not, cyberattacks.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) defines a cyber attack as:

An attack, via cyberspace, targeting an enterprise’s use of cyberspace for the purpose of disrupting, disabling, destroying, or maliciously controlling a computing environment/infrastructure; or destroying the integrity of the data or stealing controlled information.

Based on this definition, many disinformation operations include or are themselves cyber attacks. Whether it’s hacking a legitimate organization’s website to post fabricated statements, infiltrating a person’s email inbox to exfiltrate and leak data, or even using false information as a lure in phishing emails — disinformation and cyberattacks are often combined to reach the same targets and exacerbate the effect of the other.

The impact of disinformation – Foreign Relations

At the right time with the right message, disinformation has a rippling effect that can completely alter the dynamic of geopolitical relations.

Take what happened in the 2017 Qatar diplomatic crisis. In May 2017, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) allegedly orchestrated the hacking of Qatari government and social media sites to post false quotes attributed to Qatar’s emir. The quotes, among other things, praised terrorist groups such as Hamas and called Iran an “Islamic power.”

Citing the emir’s purported quotes, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt immediately banned all Qatari media, broke relations with the country, and declared a trade and diplomatic boycott against Qatar for alleged support for terrorism and relations with Iran. The alleged hacking incident, which the UAE denies any involvement in, resparked the feud among the gulf states and had massive consequences on Qatar’s economy. The embargo lasted for three and a half years, and relations between Qatar and the four other Gulf states were only restored in January 2021 after months of negotiations.

The UAE and Qatar have a history of animosity, and the UAE has previously accused Qatar of supporting Islamic terrorist organizations. In this situation, the UAE allegedly planted false information to provide a pretext for its own boycott and to give other Gulf states a concrete reason to take action against Qatar. The effects of this disinformation campaign exemplify how information can be manipulated to have a large impact on geopolitical stability and advance a country’s interest.

The impact of disinformation – Domestic Relations

While the cyber disinformation operation targeting Qatar was intended to stoke foreign discontent, disinformation campaigns are more frequently used to influence domestic audiences.

Russian disinformation campaigns

For example, in March 2021, suspected Russian threat actors hacked into the websites of Poland’s National Atomic Energy Agency and Health Ministry to spread false statements about a non-existent radioactive threat. The goal was to stoke panic among the Polish population by impersonating a legitimate and trusted institution to spread disinformation. Additionally, in an effort to expand the reach of the disinformation and give it an added appearance of legitimacy, the threat actors also hacked the Twitter account of a journalist who has historically reported on Russian and Eastern European affairs.

Russian malinformation campaigns

Another Russian cyber operation aimed at Poland took place in June 2021, but this time it was not a disinformation campaign — it was a malinformation campaign. The June 2021 attack campaign targeted the email accounts of some of the most important Polish government officials. One target was Michał Dworczyk, the head of the Chancellery of the Polish Prime Minister and the primary coordinator of Poland’s COVID-19 response.

The Russian threat actors leaked emails and documents from Dworczyk’s inbox – some of which he claims were altered and fabricated – on a Telegram channel and also through the hacked Facebook account of Dworczyk’s wife. Polish officials attributed the intrusion and leaks to the Russian Federation and stated the goal was to destabilize Poland and damage its relationship with other countries and the EU.

This is an example of malinformation because the threat actors stole real emails and information, but released them at a time and in a manner intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the Polish government. They also included a few fraudulent or falsified documents with the legitimate ones in an effort to cause more confusion and further blur the lines between what’s true and what’s false.

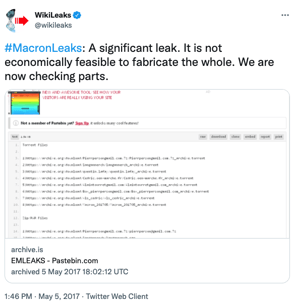

But combining malinformation and disinformation is not always successful. During the French presidential elections in 2017, a Russian-led cyberattack targeted frontrunner Emmanuel Macron. The attack included hacking into the email account of his campaign and leaking nine gigabytes of data on the internet. The more than 20,000 emails were dumped two days before the vote and just hours before the pre-election media blackout required by French law began. The hackers’ goal was to reduce the likelihood of Macron being elected. The information was shared by Wikileaks and spread on Twitter and 4chan, largely by American far-right activists.

Among the data released were some poorly forged documents and planted false information. However, rather than creating more of a scandal, the fake documents were so poorly fabricated that it cast doubt on the validity of all of the leaked documents. In effect, the “Macron leaks” operation did not have nearly as much influence on the election as intended, and Macron was still elected president.

Among the data released were some poorly forged documents and planted false information. However, rather than creating more of a scandal, the fake documents were so poorly fabricated that it cast doubt on the validity of all of the leaked documents. In effect, the “Macron leaks” operation did not have nearly as much influence on the election as intended, and Macron was still elected president.

Everyone needs to play a role

While this article discusses many aspects of mis/dis/mal-information, it doesn’t cover the efforts needed to counter these attacks or the challenges of trying to regulate online activities and social media. Combatting online disinformation requires a wide range of actors, including individuals, corporations, and governments, to work together in the effort to find practical solutions to the problems brought by this new era of information warfare.

We, as members of the public, need to be aware of the proliferation of disinformation and efforts to influence opinion, and we should think more critically about the information we encounter and consume.

Research and analysis organizations should address knowledge gaps in relation to disinformation, such as how it moves across platforms, its real-world impacts, and the tradeoffs of regulating online speech. By making specific facts unambiguous, research organizations give governments and technology platforms concrete justification to develop legislation and regulation.

Governments and social media platforms should collaborate and figure out how to balance countering online disinformation while still preserving free speech and expression. The EU’s voluntary Code of Practice on Disinformation, which is a co-regulatory instrument outlined in the Digital Services Act, is a step in the right direction in fostering cooperation between government authorities and digital platforms as well as encouraging action while avoiding crossing the line of censorship. It is important efforts such as these be expanded and replicated in order to deal with the online disinformation landscape.

All in all, mitigating disinformation threats is not an easy task. It requires a concerted effort from the whole of society to address the vulnerabilities that threat actors continue to exploit in their influence operations. Only together will we be able to counter the disinformation infodemic that continues to plague our society.

.png)