By Jonathan Lepore

NOTE: This is part 1 of 3 of this DNS Tunneling series. Be sure to check out part 2 ("A glimpse into glimpse") and part 3 ("The siren song of RogueRobin").

Intro

DNS tunneling is an abuse of the DNS protocol that provides adversaries with a covert communication channel. The prevalence of DNS traffic, coupled with the option of using the native DNS architecture to avoid direct connections with malicious infrastructure, make DNS tunneling an attractive protocol for adversaries to abuse.

In order to better understand and detect the threat of DNS tunneling, the IronNet Threat Research team analyzed several samples of malware that use DNS tunneling and the evasive tactics used by each specific malware. In this blog post, the IronNet Threat Research team examines the PoisonFrog malware that is written in PowerShell and has been associated to OilRig/APT34.

Sample

| Sample | MD5 Hash |

| PoisonFrog (dUpdater.ps1) | 477296cc6b85584f0706d2384f22b96e |

Overview

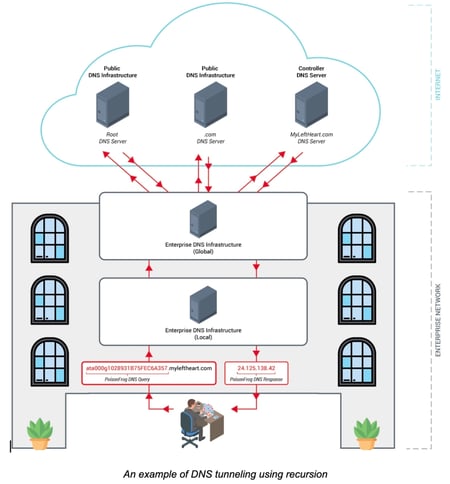

At the most basic level, malware that employs DNS tunneling needs to be able to both generate and receive crafted DNS queries and responses. These messages allow the malware to register with its controller, check for tasking, send and receive files, communicate results, and carry out other tasks. This method of command and control requires the attacker to have control over both the malicious domain and an authoritative DNS server. The use of DNS communications within malware can vary. For example, some communications make direct connections to controllers while others opt to use recursion, allowing for a natural flow across the victim’s DNS infrastructure. PoisonFrog uses the latter; recursion enables the DNS communications to traverse the DNS architecture of the victim’s environment and avoids direct connections to the controller. The diagram to our right is a contrived example of a recursive architecture.

At the most basic level, malware that employs DNS tunneling needs to be able to both generate and receive crafted DNS queries and responses. These messages allow the malware to register with its controller, check for tasking, send and receive files, communicate results, and carry out other tasks. This method of command and control requires the attacker to have control over both the malicious domain and an authoritative DNS server. The use of DNS communications within malware can vary. For example, some communications make direct connections to controllers while others opt to use recursion, allowing for a natural flow across the victim’s DNS infrastructure. PoisonFrog uses the latter; recursion enables the DNS communications to traverse the DNS architecture of the victim’s environment and avoids direct connections to the controller. The diagram to our right is a contrived example of a recursive architecture.

PoisonFrog DNS Invocation and Resource Records

PoisonFrog uses the .NET method [System.Net.Dns]::GetHostAddresses to issue command and control related DNS queries. These queries send data to their controllers through the use of encoded subdomain labels in a DNS query. For PoisonFrog’s communications an “A” resource record query is used, however this presents various limitations. For instance, PoisonFrog’s receive functions are limited to the first three octets of a DNS A record. Since only three bytes can be received at a time, transferring large amounts of data will result in a burst of many DNS queries over a short period of time. Transfering a single kilobyte of data in this mode would generate several hundred DNS queries.

It is interesting to note that the .NET method GetHostAddresses has the ability to return an array of IP addresses. PoisonFrog could have easily reduced the number of DNS replies need to transfer data by providing several IP addresses in a single DNS response. Due to the 512-byte limit on non-EDNS responses, the adversary need only ensure that responses are kept below this limit to prevent data truncation or the need to switch to TCP communications. For unknown reasons, the adversary did not take advantage of this more efficient method of data transfer in the version analyzed, opting to process only the first IP address received.

Despite DNS being a mechanism for covert command and control, it should be noted that most sophisticated malware will have a backup plan. Should the malware be unable to communicate over DNS, PoisonFrog comes packaged with an HTTP-based version of itself which runs concurrently with the DNS tunneling PowerShell script. The IronNet Threat Research team will examine PoisonFrog’s HTTP command and control in a future post.

Analysis of PoisonFrog DNS Tunneling

The core functionality of PoisonFrog DNS tunneling is to download or upload files and execute PowerShell commands sent as tasking by the controller. It is worth noting the PoisonFrog installer contains a Powershell script (hUpdater.ps1) capable of limited command and control via HTTP. However, for the purpose of this post we will focus on the DNS tunneling capabilities.

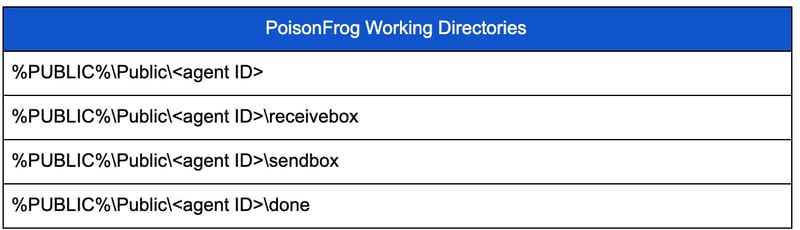

At its core, PoisonFrog is a PowerShell script designed to be invoked every ten minutes by setting itself up as a Windows task. Each time the script is invoked, it creates a DNS query to announce its presence to its controller and checks to see if there are any tasks to be performed. It then processes tasks and sends the results back to the controller. Additionally, it sets up several working directories which it uses for file-based operations. Examples of these working directories are shown in the table below.

Communications with Controller

PoisonFrog relies solely on DNS A records for communications. These communications are issued via calls to .NET class method [System.Net.Dns]::GetHostAddresses. To receive tasking, PoisonFrog generates DNS requests and interprets the received IP address responses. Once tasking is received, it processes the tasks and sends the results back to its controller. This process is performed via more complex, specially-crafted DNS requests.

To build a DNS query properly, PoisonFrog first generates an agent ID used for building all future DNS requests. The generation procedure involves using the first ten characters of the string “atag121234567890,” where UUID is obtained from a WMI query for Win32_ComputerSystemProduct’s UUID property, after removing dashes.

A DNS request is built by calling a function with several parameters. The most important parameters are the action, the payload, an associated file name, and whether the malware is sending tasking results or receiving tasking. When calling the function to create a request for tasking, the payload and associated file names are empty. These parameters are populated only when sending results back to the controller, a process which will be discussed later in this article.

Checking For and Receiving Tasks

For requests to receive or check for tasking, PoisonFrog builds a query in the following format:

[control data][management data].[domain]

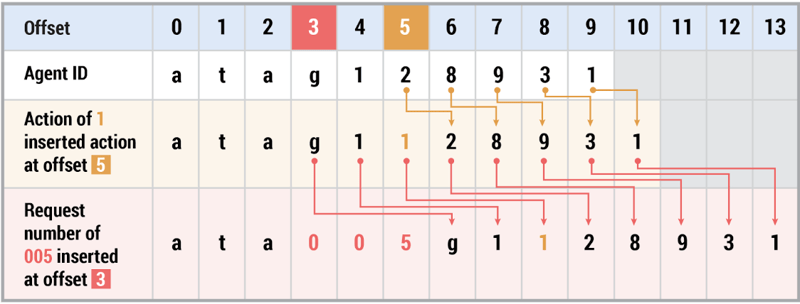

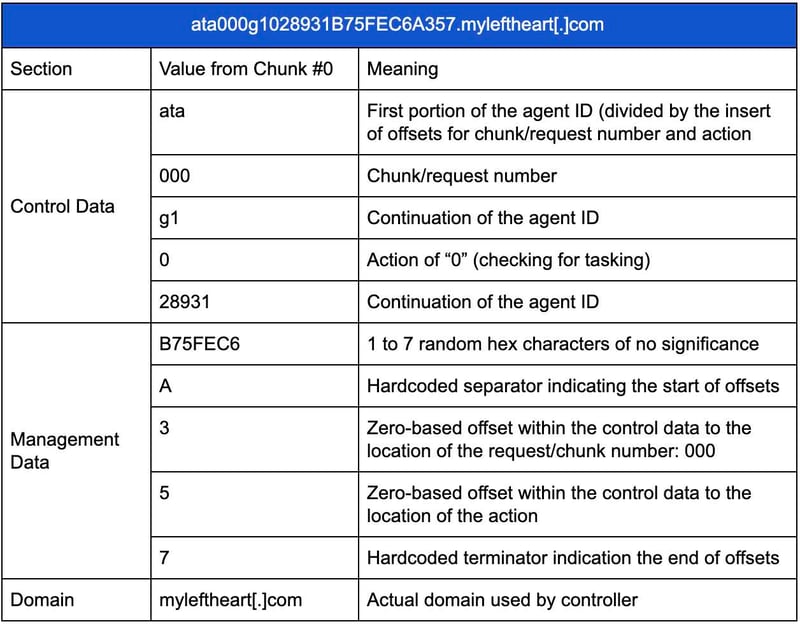

Here, [control data] is the agent ID into which a one-character action and three-character request number are randomly inserted. The positions of these randomly-inserted values are subsequently embedded in management data so the controller knows where to find them.

Next, [management data] is built as follows:

[1 to 7 random hex characters]A[index of request number][index of action]7

The characters ‘A’ and ‘7’ are hardcoded separators that indicate the zero-based indices where the request number and action can be found the control data.

Consider an example DNS query of ata005g1128931B75FEC6A357.myleftheart[.]com where the offset for the request number is 005 with a chosen random offset of 3 and an action of 1 with a chosen offset of 5. PoisonFrog first inserts the action at the chosen offset and then the request number. The table below illustrates how this process is completed:

To understand the entire DNS request generated by PoisonFrog to check for tasking, consider the following example of ata000g1028931B75FEC6A357.myleftheart[.]com, which breaks down as follows:

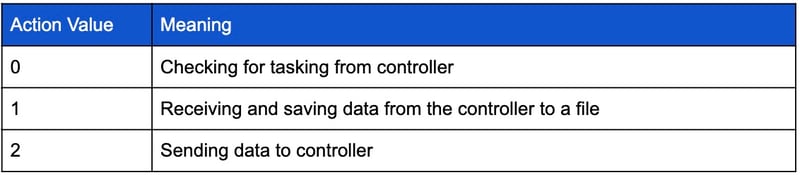

Action values indicate in which mode the malware is operating and have the following meanings:

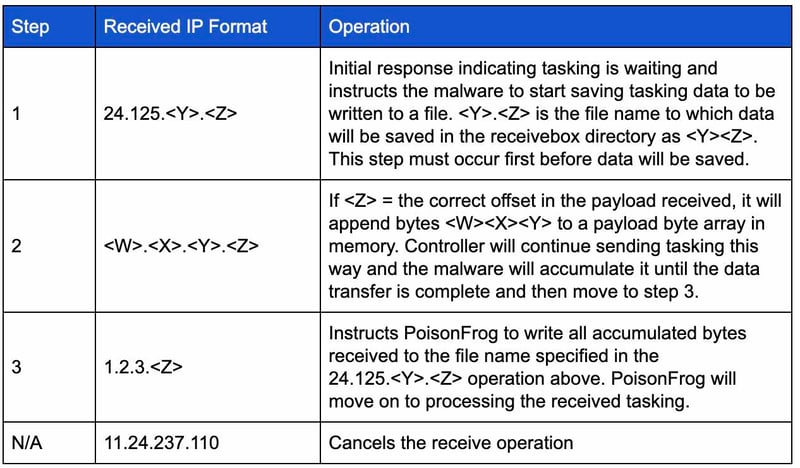

After checking for tasking, the controller will send the appropriate IP address in response. The following table shows the various IP addresses that can be sent and their meanings. In the table, the step value indicates the order in which these steps will occur to successfully transfer tasking to PoisonFrog:

Once the tasking is saved to a file, PoisonFrog will exit its receive loop and begin to process the tasking. The tasking is processed by examining the last character in the filename received in step 1 above () and performing the following operations:

Sending Task Results

After processing the tasking, PoisonFrog transmits the results back to the controller by sending the controller DNS requests encoded with the exfiltrated data. PoisonFrog then breaks up the data into smaller messages to be sent with payload chunks of up to a maximum size of 60 bytes. The controller data is sent using the DNS request builder function from above, this time in “send” mode. The send mode DNS request now includes more fields for this payload data and an associated file name, both of which are encoded using a function called “resolver” which marshals the data to be transmitted by rearranging the nibbles of each byte. The resolver function is explained in further detail below.

Once the payload has been resolver-encoded, PoisonFrog prepends the string “bWV0YT” (without quotes) to it to indicate the start of the transmission of tasking results. Next begins a loop of DNS requests, each containing a chunk of the payload until the contents have been completely transferred. To signal completion of the file transfer, PoisonFrog will issue a final DNS request containing a payload solely consisting of the string “bWV0YTZW5k” (without quotes). When transmitting tasking results to the controller, an action mode of “2” is used.

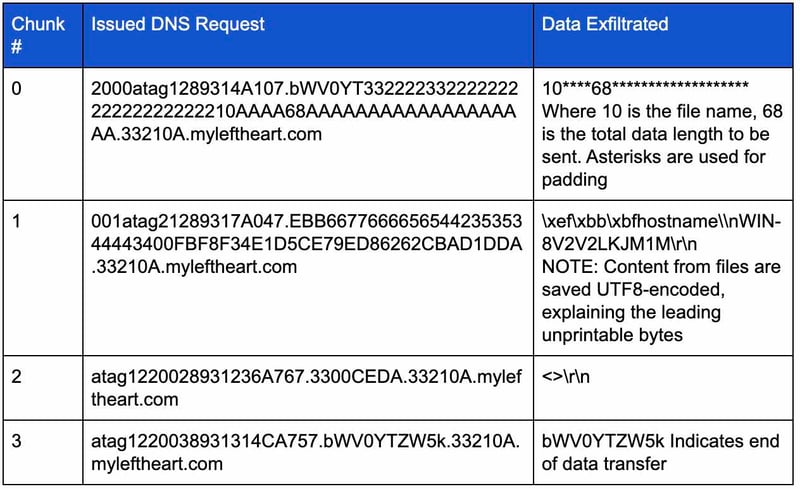

The table below shows an example of the complete exfiltration of a file containing the output of the ‘hostname’ command:

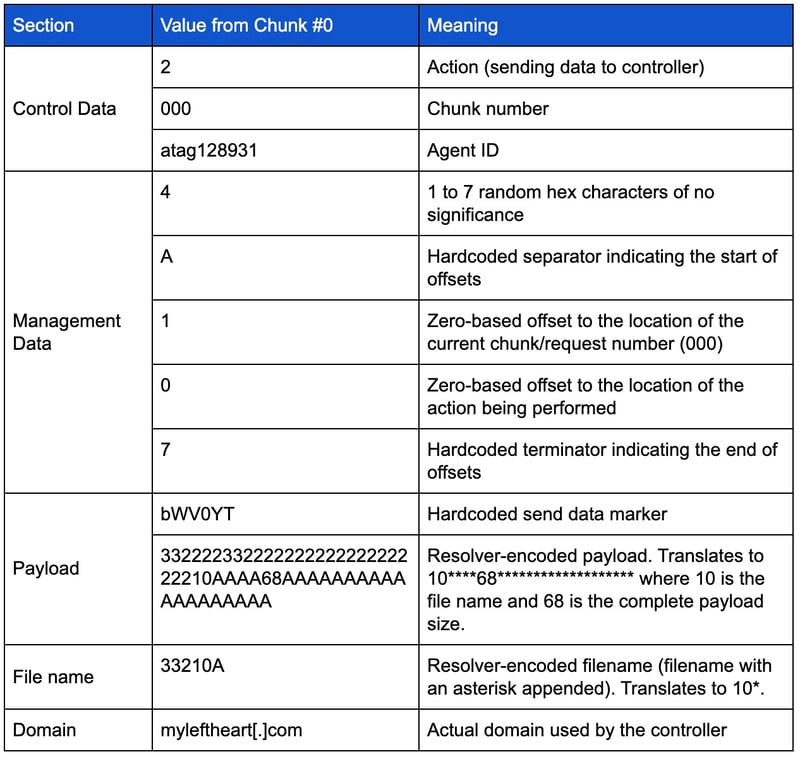

Using the example above, a more detailed breakdown of chunk #0 is provided below:

For each DNS request issued, the controller can respond with an IP address of 11.24.237.110 (indicating the transmission should be cancelled) or an IP address of the format 1.2.3.[X], where [X] is used to request sending the next chunk of data.

Resolver Function - Data Marshaling Strings/Byte Arrays

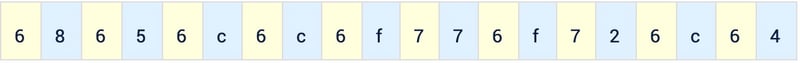

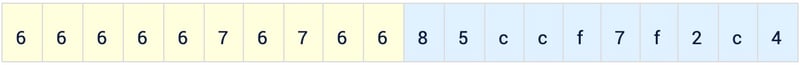

PoisonFrog prepares its payload and filename data for transmission using a function called resolver. This function takes 30-bytes at a time and extracts the first nibble of each byte and concatenates them together. Next, it concatenates the second nibble of each byte and appends that to the first string. This is repeated until the data is consumed. For example, consider the string "helloworld" in the example below:

The original byte stream for this is:

The resulting byte stream is rearranged as follows:

Conclusion

Malware communications today can use a number of web-based protocols to communicate with C2 servers. While HTTP, TLS, and other protocol abuse may get more attention in the news, our analysis of PoisonFrog shows how DNS Tunneling is still an effective means of covert communications. While PoisonFrog is a fairly standard malware that does not leverage sophisticated scripting or specific vulnerabilities, it can still be highly effective in evading detection by firewalls, endpoints, proxies, or other signature-based or outlier-based network controls since adversaries can easily change or rotate domains, IPs, and hardcoded values to a range of stable destinations that are not identified or categorized as malicious by domain reputation or threat intel sources. Consistently detecting adaptive malware such as PoisonFrog, will require a behavioral analysis solution and that can identify underlying network communication patterns.

In our next blog, we will examine the DNS Tunneling capability of Glimpse, which also has been linked to the OilRig/APT34 threat group.

Go to DNS Tunneling: part 2 ("A glimpse into glimpse").

Follow the IronNet Threat Research team @IronNetTR.

.png)